[ad_1]

Our first morning game drive from Porini Mara Camp is the sort of experience wildlife lovers dream of their entire lives. We’re exploring the Ol Kinyei and Naboisho Conservancies, on privately-owned Maasai land bordering the Maasai Mara National Reserve in southern Kenya.

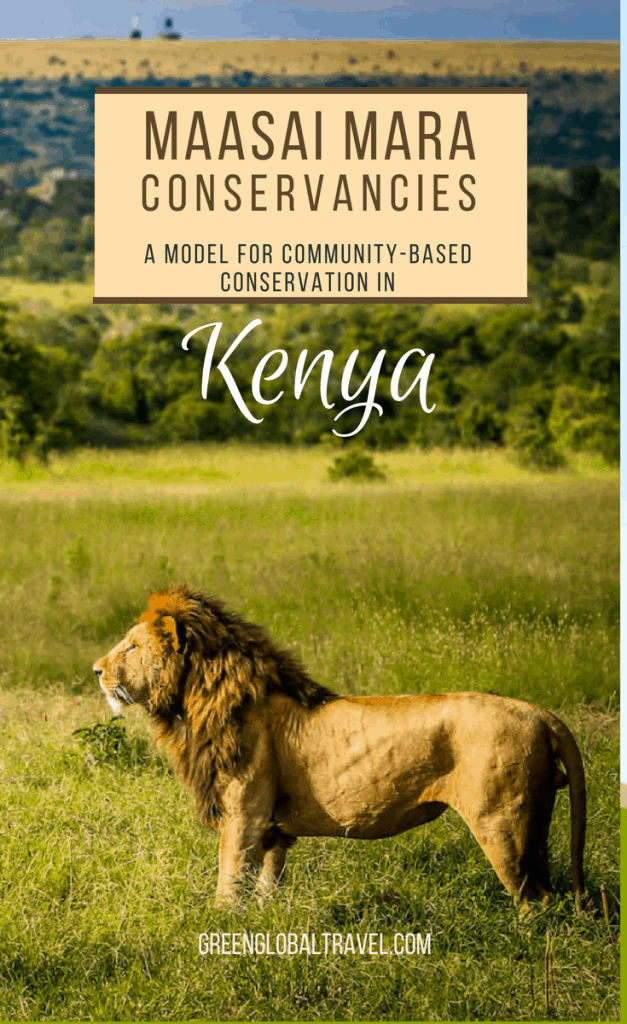

The day begins with an exceptional sighting just after sunrise. A massive male lion, his lush mane blowing in the gentle breeze of the open plain, nibbles on the vestiges of a wildebeest kill. He takes his time, savoring every bite and licking the meat almost like a lioness grooming her cub.

As he slowly saunters off, finally satiated, we count no less than three dozen hyenas, several tawny eagles and white-backed vultures, and a scrappy pair of black-backed jackals moving in. All of them divvy up the remaining scraps of carcass in a loud and frantic feeding frenzy.

On my four previous African safaris, this hour-long introduction to the animal kingdom’s pecking order would have proven the trip’s most memorable scene. But in the Maasai Mara, where predators and prey are plentiful long before the Great Migration begins, this wasn’t even the highlight of our morning.

On our way back to camp, we round a corner to find a cheetah resting atop a rocky mound in front of a watering hole. As our Maasai guide, Wilson Saningo, moves the vehicle to get a better vantage point, we see two 16-month-old cubs napping on the other end.

All three cats are thin, sluggish, and appear to be hungry.

A herd of zebras cautiously heads towards the watering hole, warily watching the cheetahs every step of the way. They approach strategically: Most stay in front as small groups go back to drink. Strangely, the cheetahs seem only mildly interested. But as soon as the zebras leave, the mama begins to move.

We follow them from a distance, surprised to see them heading opposite the direction of the zebra herd. Until this point we’ve mostly had the cheetahs to ourselves. But suddenly two other vehicles appear out of nowhere, diverting the cats from their hunt.

Wilson chastises them for not giving the animals enough space. It’s the first time we’ve ever seen a guide call out another guide’s irresponsible behavior.

As Wilson peers through his binoculars, he sees the cheetahs on the run. “Hold on!” he says, and suddenly we’re hurtling across the plain, deftly avoiding small acacias but catching air as we hit the occasional volcanic rock.

We arrive on the scene just in time to see the trio take down a male Grant’s gazelle, with the mother cheetah crushing its windpipe as one of the cubs begins to feed.

By the time we leave them to their feast, we’ve spent more than two hours watching the cheetahs, much of it without any other tourists in sight. After spending 60+ days in Africa, this exclusive experience leaves us exhilarated and eager to see what other wildlife wonders our four days in the Maasai Mara will bring.

READ MORE: Animals in Kenya: A Guide to 40 Species of Kenyan Wildlife

- Maasai Mara History

- The Conservancy Concept

- Ol Kinyei Conservancy

- Olare Motorogi Conservancy

- Conservancies & Conservation

- Community Outreach Programs

MAASAI MARA HISTORY

The nomadic Maasai people had been grazing their animals on the vast plains of East Africa for around 200 years before the first European explorer showed up in the early 1890s. They knew the area as siringet, “the place where the land runs on forever,” which led to the establishment of the Serengeti Game Reserve (now Serengeti National Park) in northern Tanzania in 1921.

The Mara, which borders the Serengeti in southwestern Kenya, was named after the Maasai word for “spotted.” It’s an apt description for the seemingly endless savanna landscape, which is dotted by circles of trees around watering holes, cloud shadows, and acacia scrub.

The Maasai Mara started as a 200 square mile wildlife reserve in 1961, ultimately achieving protected National Reserve status in 1974. The reserve has since been expanded to cover some 583 square miles. But these days it’s just a small part of the Greater Mara Ecosystem, which also includes Ol Kinyei, Naboisho, Olare Motorogi, and various other privately owned conservancies.

The area is best known for the Great Migration, which is widely considered among the world’s Top 10 Natural Wonders. Every year millions of gazelles, wildebeest, zebras, and other ungulates make the arduous 500-mile trek north to Kenya in order to follow the seasonal rains (and the tasty red oats that grow in their wake).

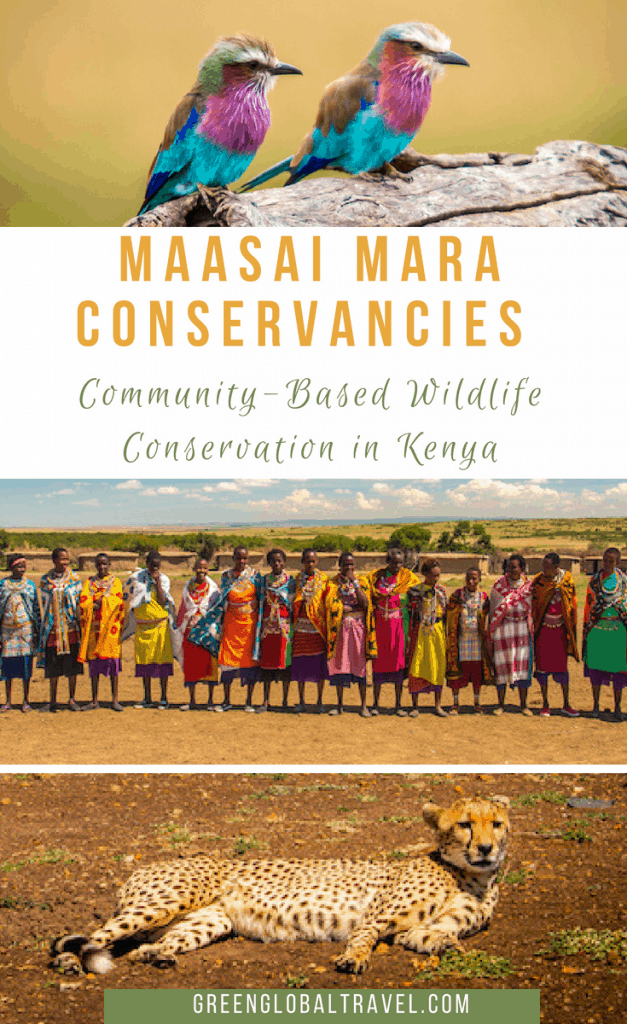

The famous crossing at the Mara River, where hungry crocodiles lie in wait, is unlike any other African safari spectacle you’re likely to see. But the Maasai Mara offers numerous attractions at other times of the year, including a high density of big cats, elephants, buffalo, and more than 470 different species of birds.

Unfortunately, much of the news out of the Maasai Mara over the past few decades has not been positive. A WWF-funded study (conducted 1989 to 2003) found that ungulates– the hoofed animals predators rely on for food– were on a steep decline due to human encroachment and poaching. Populations of impala, giraffes, and warthogs in the reserve declined by 67 to 80%.

It would be unfair to blame the Maasai people for the Mara’s issues. They’ve battled for rights to their ancestral lands for decades. They endured 40,000 people being forcefully relocated after their land in Tanzania was sold to foreign investors in 2009. And they narrowly avoided having a 31-mile road built through the heart of the migration route across the Serengeti in 2011.

Fortunately, private tourism companies began working with community leaders to help the Maasai develop a new, sustainable model for community based conservation that’s benefiting locals and wildlife alike.

READ MORE: Embracing the Culture of the Maasai People

THE CONSERVANCY CONCEPT

As declining wildlife populations and mass tourism have become more problematic in the Maasai Mara National Reserve, the conservancies that border it have become increasingly vital. In fact, community conservancies encompass over 10% of Kenya’s land– more than all of the country’s national parks and reserves combined.

According to Gamewatchers Safaris & Porini Camps Managing Director Mohanjeet Brar, “60 to 70% of Kenya’s wildlife is found outside protected national parks and reserves. So if we want their populations to continue to flourish, we need the local communities involved and benefiting in a meaningful way.”

Gamewatchers founder Jake Grieves-Cook (a Kenya native who formerly served as Chairman of both the Ecotourism Society of Kenya and Kenya Tourism Board) was one of the early pioneers of the community conservancy concept in Kenya more than 20 years ago.

He started in Selenkay, an important wildlife dispersal zone outside Amboseli National Park. There was rampant hostility against animals there in the 1970s and 1980s. There were attacks on migrating elephants, snaring of wildlife to eat or sell as bush meat, and slaughtering of predators that preyed on livestock.

Grieves-Cook signed his first agreement with the Maasai in 1997, establishing the Selenkay Conservancy on 14,000 acres of privately owned land. In exchange for lease payments, bed night and entry fees and employment opportunities the locals agreed to help conserve the area’s wildlife.

In return, Gamewatchers got the rights to build low-impact safari camps and provide exclusive experiences for their guests.

This is what Brar calls a “triple bottom line approach– a business that benefits the environment, communities, and company.”

The company built on their Selenkay success by setting up the 18,700-acre Ol Kinyei Conservancy in 2005 and the 22,000-acre Olare Oroki Conservancy in 2006. Two more conservancies– the 11,000-acre Motorogi and 50,000-acre Naboisho– followed, with the former later combined with Olare Oroki to create the 33,000-acre Olare Motorogi Conservancy.

READ MORE: 50 Fascinating Facts About Giraffes

All of their small Porini Camps are extremely low-impact in terms of environmental footprint, with a maximum of 12 tents per camp. “Jake developed a standard [where] every tent we put up has to pay towards protecting 700 acres of habitat,” Brar says. “So a camp of 10 tents is paying to protect 7000 acres of land. This in turn limits the number of vehicles to about 1400 acres per vehicle.”

Approximately 95% of the staff in their conservancies and camps– including around 245 game wardens, guides, trackers, hosts, and camp managers– come from the local communities.

In terms of revenue, the Maasai are expected to generate over $1.5 million from the conservancies in 2018, with more than 1,000 families receiving monthly payments.

According to Cynthia Moss, the iconic conservationist behind the Amboseli Trust For Elephants, “The establishment of the conservancies in Kenya has been the single most successful conservation initiative since the creation of national parks in the 1940s.”

READ MORE: The Importance of Community-Based Tourism in Responsible Travel

OL KINYEI CONSERVANCY

The smallest of the three Maasai Mara conservancies, Ol Kinyei is unique in that Gamewatchers has exclusive rights to offer game drives on the land.

There are just two permanent safari camps there, Porini Mara and Porini Cheetah, each of which accommodates a maximum of 12 guests. They also offer two small, mobile camps– Porini Bush Camp and the more budget-friendly Gamewatchers Adventure Camp– during the high season.

As a result of this limited access to the conservancy, Ol Kinyei’s terrain– which varies from verdant rolling hills to savannah plains spotted with whistling thorn acacia– is impressively pristine.

Migrating herds of ungulates are drawn here from Kenya’s Loita Plains early in the year due to numerous rivers, springs, and streams running through the conservancy.

We see Ol Kinyei’s herds immediately upon our arrival. Zebras, wildebeests, and topis (a.k.a. blue jean antelopes, due to their distinctive leg markings) were nowhere to be found among the tall grasses of the Maasai Mara National Reserve.

But here we see them regularly, with lots of youngsters from the annual calving that occurs in February and March.

Predators– including cheetahs, leopards, and a 20+ member lion pride– are drawn here by the herds. We see a 5-year-old bachelor male from this pride on our first evening game drive in Ol Kinyei, missing part of his tail due to a confrontation with another lion.

Spotted hyenas and black-backed jackals are not in short supply either. The hyenas live in matriarchal groups more like those associated with primates: They hunt as a pack, but dominant members compete for eating and breeding rights.

The jackals mate for life, and hunt cooperatively.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about our two days in Ol Kinyei is how many of our most memorable sightings come with no other vehicles around.

Our engagingly enthusiastic driver/guide, Wilson, grew up in this area and has an uncanny knack for finding the animals. He also seems to understand how to position the vehicle in order to get the perfect photographic angle.

In addition to the aforementioned cheetah kill, there’s a bush breakfast by a watering hole, where two massive hippos battle over territory. There’s a huge herd of elephants that surround our vehicle as they cross the road, with a baby 10 feet away who flaps his ears in mock threat.

But my favorite sighting is a mini-migration just before sunset on our last night in Ol Kinyei. We’re surrounded by hundreds of wildebeests, a herd of zebra, and several dozen giraffes.

They’re all making their way south across the plain, where they will ultimately rendezvous with their cousins coming north from the Massai Mara National Reserve. It looks like a scene cut straight from The Lion King.

OLARE MOTOROGI CONSERVANCY

Olare Motorogi, which directly borders the Maasai Mara National Reserve, is an excellent example of how the conservancy concept can help once-exploited ecosystems recover.

Until 2006, this area was overgrazed by cattle, destroying the habitat on which both humans and wildlife depended. By transitioning to carefully controlled grazing rotations and a monthly rental system, ecotourism has now become a long-term sustainable revenue stream for locals.

Encompassing acacia woodland, the lower valleys of the Olare Orok and Ntiakitiak rivers, riverine forest, the Ntiakitiak Gorge, and a 12-kilometer escarpment, the conservancy is the best place to see the Great Migration if you want to avoid the crowds of tourists in the Massai Mara National Reserve.

The area is renowned for its remarkable predator density. In a 2016 scientific paper, Oxford University researcher Nic Elliot (director of the Mara Lion Project) found that the Mara ecosystem boasted the highest lion density in all of Africa. They estimated approximately 17 lions per 100 square kilometers.

We get a taste of this bounty during our first game drive in Olare Motorogi, coming upon a group of 13 lionesses and cubs next to a river just before sunset.

Gamewatchers shares this conservancy with several other safari camps, so we have to wait our turn to get close. But with no more than five vehicles allowed at any sighting, we get plenty of time to photograph the dozing cats.

The next morning, wildlife sightings come with increasing regularity. There are herds of elephants, skittish Cape buffalo, and giraffes feeding on acacia leaves, oblivious to our proximity. A humongous hippo crosses an open field, presumably having lost a battle for territory.

Birds of prey ranging from African fish eagles and white-backed vultures to bataleurs sit perched in tree tops and along riverbanks, waiting to snatch a meal. But it’s our second evening game drive that ultimately proves to be the most memorable of our two days in the Olare Motorogi Conservancy.

Jackson Sayialel, the head guide at Porini Lion Camp, offers unspoken lessons on the benefits of patience and persistence when on safari. As we make our way towards a distant part of the conservancy, he spots a half-dozen vultures in the trees above an area dense with grass and acacia. “It appears as if there has been a recent kill,” he says as we slowly search the surrounding brush.

About 20 minutes later we find it: The corpse of a Cape buffalo down in a gully, with a male lion sleeping soundly beside it. He suggests we leave to go look for a cheetah with 4-month-old cubs he knows of, and then come back to the kill at sunset, when the rest of the pride may come out to feed.

As you can imagine, finding a specific animal in a 33,000-acre conservancy is akin to looking for a needle in a haystack. So it takes nearly an hour of searching before we finally spot the mother cheetah leading her quartet of adorable cubs across the plain. The result– getting to watch all five cats playing a hilarious game of chase-and-pounce around two trees– proves well worth the wait.

The lion’s still asleep by the time we return to the kill, but finally wakes up just as we raise our glasses for a sundowner toast to another incredible day in the Maasai Mara. He sends chills down our spine as he roars several times, then lazily makes his way over to the buffalo carcass and resumes feeding.

It’s difficult to explain the wistful feeling that overcomes me as we make our way back to Porini Lion Camp for the last time. Even though we planned to explore the Maasai Mara National Reserve the next day, I knew it’d be impossible to top the experiences we’d had in Ol Kinyei and Olare Motorogi. I hug my wife and daughter close, trying to savor every last moment of this special day.

It seems somehow appropriate that our dinner is extended with a surprise performance of a traditional Maasai warrior dance by the camp staff. We hear their traditional chants long before they enter the tent, and marvel at the height even the shortest men get when they leap into the air. It’s my third time seeing the dance up close, but it’s just as thrilling as the first.

CONSERVANCIES & CONSERVATION

The next morning at sunrise, we see the difference between the conservancies and the Maasai Mara National Reserve first-hand. On our way out of the Olare Motorogi Conservancy, Jackson spots a male leopard emerging from the tree line. We’re the first ones to see him, so we have the gorgeous cat to ourselves for a good 10 minutes before other vehicles arrive on the scene.

Less than 20 minutes later, as we cross the invisible boundary into the Maasai Mara National Reserve, we find 13 safari vehicles in a semicircle around a pair of mating lions. Jackson tells us that during peak season (when an average of 2,700 people visit the reserve on a daily basis), the number of vehicles around a sighting like this can easily triple.

“In terms of sustainability, it’s important to ensure that there are standards set when it comes to tourist density,” says Mohanjeet Brar, who has a doctorate in Plant Science and is certified by the Kenya Professional Safari Guides Association. Unfortunately in our national parks and reserves there haven’t been sufficient standards set. We’ve seen the damage from overtourism, where the environment, wildlife, and tourist experience suffers.”

According to University of Oxford researcher Femke Broekhuis, cheetahs are particularly threatened by the lack of tourism limits in the Maasai Mara. Due to fragmentation of natural habitat, decline in populations of their prey, the illegal wildlife trade, and human conflict, cheetahs have vanished from 91% of their historic range.

By analyzing four years of data on cheetahs with cubs, she realized that high numbers of tourists are negatively impacting the number of cubs that reach the age of independence. Females in heavily traveled areas raised an average of just 0-1 cub per litter to the age of independence, compared to more than two cubs on average in conservancies where tourist numbers are limited.

“My conclusion is that tourists are likely to have an indirect effect on cub survival,” Broekhuis writes. “This could be because they lead to cheetahs changing their behavior and increase their stress levels by getting too close, overcrowding with too many vehicles, staying at sightings for prolonged periods of time, and by making excessive noise.”

Her suggestions for improving the situation in the Maasai Mara may sound familiar:

- limiting tourist numbers;

- allowing no more than five vehicles at a cheetah sighting;

- ensuring that vehicles keep a minimum distance of 30 meters at a cheetah sighting;

- ensuring that noise levels and general disturbance at sightings are kept to a minimum;

- ensuring that vehicles do not separate mothers and cubs; and that

- cheetahs on a kill are not enclosed by vehicles so that they can’t detect approaching danger.

So when our guide, Wilson, chastised those drivers from the other safari camps in the Naboisho Conservancy for getting too close and diverting the cheetahs from their hunt, he was speaking for the animals. Which may explain why we saw a dozen cheetahs during our four days in the conservancies, and not a single one during our day in the reserve.

COMMUNITY OUTREACH PROGRAMS

During our time in the conservancies, I had a chance to interview Game Warden Simon Nkoitoi (who also grew up in the Mara) about how the conservancy partnership helped with wildlife conservation. He emphasized the three-pronged connection between the company, the community, and the ecosystem.

“The community benefits off of their land, receiving income from leases,” he said. “Just this morning we gave about $1.4 million in shillings (equivalent to $14,000) in scholarships for school children, which is additional income.”

“The Maasai have a cattle culture,” he continued, “and lions sometimes attack their livestock. If they do, the company will thank the community for not killing the animal by building a lion-proof boma. Then the Maasai will be happy and sleep through the night, because they don’t have to watch out for lions with a flashlight.”

Building bomas is just one of many community outreach programs that Gamewatchers Safaris & Porini Camps have developed to address the core concerns of conservation, education, and water:

- Ilmonchin School Sanitation Project -In rural Kenya, water, sanitation, and hygiene are huge issues. For this project, the company has partnered with UK-based NGO Dig Deep to help provide adequate toilet facilities for a primary school in the Ol Kinyei community.

- Ol Kinyei Bursary Fund -Although primary education in Kenya is free, parents often incur the costs for thing such as uniforms, books, school activities, and school rehabilitation projects. Thus fund helps to cover those additional costs, providing under privileged youth with the education they need to build healthy careers.

- Koiyaki Guiding School Scholarship Fund -Almost every guide we had during our time in the Mara conservancies (including Wilson and Jackson) was a graduate of this school, which provides professional tourism training for the Maasai. This scholarship was created to help students who are passionate about wildlife conservation, but cannot afford the Naboisho-area school’s fees.

[ad_2]